LOS ANGELES “THE BLACK CAULDRON” Walt Disney's $15 million animated film scheduled for 1980 — is four years behind schedule. It will not be completed until Christmas, 1984, because the new crop of young animators the studio has spent six years acquiring are not yet competent to handle its complexities. “The Black Cauldron,” which is based on Lloyd Alexander's interpretations of medieval Welsh mythology, will be replaced in 1980 by a simpler and easier movie about animal friendship, “The Fox and the Hound.”

At the same time that Disney's young animators are floundering in waters still too deep for them, classic Disney animation is enjoying a surprising artistic and box‐office renaissance.

The re‐release of Disney's 1967 “The Jungle Book,” is bringing the studio $14 million, $2 million more than the picture made when it was first released 11 years ago. And the studio's last animated film, “The Rescuers,” is outdrawing “Star Wars” in Paris, as an adult cult film in Western Europe, it has earned $45 million for the studio, and has recently become the largest grossing picture of all time in West Germany.

Mickey Mouse Turning 50

But the last Mickey Mouse cartoon was made in 1953; and only ‐two of the nine young men who cut their artistic teeth on “Snow White” in 1938 are still at the studio.

“We never get old, never die, never retire,” said 73‐year‐old Eric Larson. “We accepted that and the studio accepted it. They never looked beyond us. “

Pompousness ‘Rewarded’

“I worked the first two weeks for nothing and then got $15 a week. There was no pay for overtime and no air conditioning.

We stripped to the waist in the summer and if a guy was taking himself too seriously we'd stick a flutter pad under his seat so he'd make rude noise when he sat down. There were 180 people at the studio, including the night watchman and the janitors. Today, it's a corporate structure, large and complicated place.”

Walt Disney called them his nine old men: Les Clark, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, Mr. Kimball, Mr. Larson, John Lounsbery, Wolfgang Reitherman and Frank Thomas.

“The Rescuers,” exactly 40 years after “Snow White,” is the last film to bear their stamp. Mr. Lounsbery directed “The Rescuers.” Mr. Thomas and Mr. Johnston animated the mice—Bernard and Miss‐ Bianca — in the months before their retirement. Mr. Kahl drew the villainous Medusa and her 2 alligators and also retired.

Talent‐ Search Is Unproductive

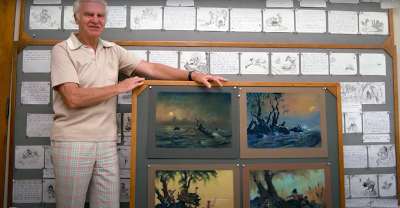

When his nine old men really became old. Walt Disney was dead; and his studio was unprepared. A talent search begun by Mr. Larson in 1972 has brought surprisingly meager results.

“We'd like (to add) 30 good animators,” he said. He has looked at thousands of portfolios and tried out 100 young animators in the last six years. Of those, 35 remain; and only 16 are in animation. “When someone is hired, you can't tell how good he'll be,” Mr. Larson said. “ Animation is limited only by imagination and the ability to draw what you can imagine.

“People come with master's degrees in art and they can't draw worth damn. Art teachers are interested in static figure drawing. We deal with weight, action, movement. You have to be able to draw the relationship of character's coat to the rest of his body or the relationship of his cuffs to the rest of his coat.”

Conception of Space Vital

“A person can show you drawings that knock you out,” said Mr. Kimball, “but he may not have a conception of movement, may not be able to put something in a space. And there are more choices today. A lot of young animators don't want to work here, don't want to knuckle down to the training required of Disney animators.”

Disney has its own reservoir in the animation school it has set up at the California Institute of the Arts to teach the Disney style of animation. Yet, out of 19 portfolios from Cal Arts this year, Mr. Larson found only two good. “And three more are passable.” The special skills required in animation mean that, in the movie business, where nepotism is a way of life, there is almost never a second‐generation animator. Mr. Larson can think of only one, John Kimball, Ward Kimball's son.

Disney's Death a Blow

The death of Walt Disney in 1966 was a special blow to his animators. Movies — regarded as the most collaborative of arts — seem a hermit's paradise next to the number of people required to create the 129,000 drawings used in an animated feature. “Walt had such an ego, he was so tremendous, that he could weld us into a team,” Mr. Larsbn said. “It's a big problem for these new people to become a cog in a team effort. They want to be in ‘the industry,’ not at this particular studio. There was a loyalty to this particular place. And I'm not sure we can renew it.”

“I don't think there has ever been an artistic medium that requires as many people,” said Mr. Reitherman, who is directing “The Fox and the Hound.”

“It's definitely a team sport. But how do you train a young animator? A feature film is very expensive. ‘The Fox and the Hound’ will cost $8.5 million. And it's four years of pregnancy before it's finished. We used to make 24 shorts a year. We don't have that way to train people anymore.”

Shorts Were Great School

“I was at the studio five years before Walt made his first feature,” said, Ward Kimball. “We made six or seven minute shorts. What a great school to break in new animators. You could see your work on the screen in weeks.”

Today, shorts lose money. The last Disney cartoon was “Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too” in 1974. Partly to give the young animators some experience, the studio is now making a 25‐minute animated short, “The Small One,” which will be released next Christmas. The director of “The Small One” is 39year‐old Don Bluth, the most highly regarded of the next generation of Disney animators.

Then the younger animators will face a New‐style Disney film, “The Black Cauldron,” requiring a whole new generation of animators (with more sophisticated characters than) the happy dog and cheerful fox of “The Fox and the Hound. The Black cauldron, is a kettle that has the ability to bring the dead to life and is guarded by three witches who can interchange themselves.

“As far as drawing is concerned, entertainment is concerned, background and layout and effects are concerned, that's terribly challenging staging,” Mr. Larson said.

“The picture also has a boy hero and a girl heroine. As soon as you start working with human figures, you let the audience compare their movements with the movements of a real person the same size. Animals and’ caricature figures like Medusa are much easier.”

What makes it all so difficult is that, beyond technical competence, there is something more important to men who speak of animation as magic rather than skill. “Animating isn't moving things,” said Mr. Larson. “It's trying to make them live.”

“Shere Khan in The Jungle Book’ didn't really look like George Sanders, the actor who was his voice,” Mr. Reitherman said. “But he had the imperious attitude, the arrogance. He was the essence of George Sanders; Eva Gabor said the tiger was more like her husband George Sanders, than Sanders (himself).

“I retired,” said Ward Kimball, “because I was beginning to get bored. Maybe subliminally I missed Walt. Without him, things weren't fun anymore.